by Fong Min Hun

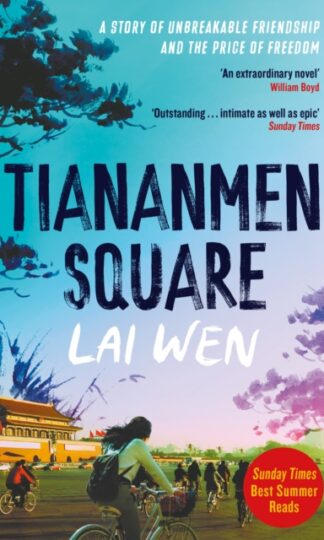

As booksellers, Elaine and I constantly work through an endless pile of books to determine their suitability for our shelves. We usually divvy up the books between us and avoid reading the same book to speed up the assessment process (which makes for interesting book conversation, because rather than discussing something we had read together, we are almost always telling each other about the book that we just read). It’s not often that we would say to the other person, ‘Hey, you need to read this book’ but she said just that after finishing Elizabeth Wong’s We Could Not See the Stars several months ago. I mumbled, ‘Okay, I’ll get around to it,’ and left it at that. But several weeks ago, she’d thrown the book at me, metaphorically speaking, and said ‘Read It!’, because the author was going to be making an appearance at our shop and I Needed To Read The Book. And so I did.

At first blush, We Could Not See the Stars is a work of speculative fiction set in an alternate Malaysia populated by emigrant Chinese in which Manglish is spoken exclusively. The story begins in Kampung Seng, a small fishing village on the west coast of the Peninsula, where our protagonist, Han, lives the quiet, unassuming life of a rural fisherman. He schleps for his rich uncle — Tauke Lim — who owns the largest fishing operation in the kampung and spends his days aimlessly rooting around, despite his young age. What sets Han apart from all others, however, is his spotty provenance: his mother, Swee, had suddenly appeared at Kampung Seng with him in tow years ago armed with a mysterious looking spade, and never disclosed any information in regards to her origins or her family. That she would then deliberately run into the sea to her death several years later, leaving no clue as to her origins save for the odd-looking spade, would further deepen the mystery of the pair.

Han, who has little recollection of his mother and even less of their past, is phlegmatic about this void in his life even though he is plagued by dreams and fragments of memories embedded in his being. All this changes when his mother’s spade is stolen from his house — “She’s dead and I have nothing left of her!” — spurring Han to go after the thief, setting him off on a journey that will take closer than ever to the discovery of the truth of his heritage. His odyssey will see him leave his tiny kampung for the first time, taking him to the Capital in the Peninsula, then across the deadly Desert of the Birds, and finally across the sea into the Hei-San archipelago where the secret of his origins lies within the forest of Naga Tua.

First, a word about the language. It is clear from the off that Elizabeth Wong is adamantly writing a book about Malaysia, for Malaysians. However, there is also no doubt that she is writing about a specific setting of Malaysia and for a specific segment of Malaysians:

In their evenings, they lingered in the parking lot of the former Golden Star cinema. The last rays of sunlight flared across their motorcycles as they smoked their cigarettes, and the dust clouds from the main road billowed around them. Sometimes they would race from Golden Star to Liu’s prawn farms on the other side of the village, and back again… If they were at Boon Chee, they would watch football matches that were showing on the twenty-year-old Sony TV that hung over the entrance, next to Laughing Buddha looking at them. ‘Eh, boss, boss, more beer, peanuts also, why like that so slow?’ Chong Meng would holler, and the workers would scurry.

Those of us of a certain vintage and variety would certainly recall such locales: Chinese townships anchored by the local cinema — the Sentosa, Paramount and Ruby cinemas come to mind — supported by an enclave of petty merchants selling sundry items and fireworks under newspapers during Chinese New Year. The local patois would very much be dictated by the majority dialect group in the area, and if any English was spoken in these areas, it would be in the Manglish so deftly illustrated in the line of dialogue above. Even the cry of the rooster, which Wong phonetically dishes out as Goukokoko, is typically Manglish; nowhere else would you find a rooster’s cry written out in this way, in the same way that so many thousands of Chinese Malaysian mums have sounded the cry of the rooster to their children.

Indeed, all of Wong’s characters speak in Manglish in the novel. Nevertheless, it is a particularly Chinese Malaysian variety of Manglish that dominates in the book which leaves the question of, ‘What about the other races?’ unanswered. The fact of the matter is, the other races don’t feature in the book at all; or if they do, their distinguishing marks are subsumed under generalities and abstractions. (White men do make an appearance in the book, although they are, perhaps slightly pejoratively, described as the White Ghosts, a literal translation of the Cantonese term for Caucasians, gwai lo [鬼佬]. Before anyone loses their composure over this, it’s a very minor role and their presence more a function of world-building demarcating boundaries than anything else).

But there is a reason for the Chinese-Malaysian-centricity of the book. At its core, We Could Not See the Stars is a fable about the Chinese diaspora, and about the descendants of those who left the motherland for Nanyang in search of riches in these relatively virgin lands. It is about those of us who have been separated from our ancestral lands for generations, who have lost all bonds of familiarity with these lands, and yet hold on to a thin thread that ties us to a past and impels us to seek out our identity by following that thread of history. This theme is repeated in several passages through the novel:

We are all part of this world, Ah-ma explained, connected in this great shining net of humanity, and to belong in it fully, one needs a past, a history.

For we are stardust — we are merely a minuscule physical manifestation of larger processes, planet forming from bits of rock and dust, plants generating oxygen, comets and asteroids delivering water, volcanoes spewing aleum, creating homes for humans to find and populate; we are one sentence in a larger story, one whose ending has not been written yet. To lose this history is death.

We Could Not See the Stars is not a perfect novel. I have some reservations about the pacing and the structure of the book, and there is a sense that the balance between world-building and plotting is slightly off-kilter. Nevertheless, the book continues to resonate deeply within me because the problem of historicity and identity is one that I can strongly identify with. Going back to the metaphor of the thread of history which ties us to our past, we can also see that the thread thins and weakens with each successive generation. There will be a point of inflection in which the thread snaps altogether, and decisions will have to be made: about when and where we are to re-anchor ourselves, and to decide our part in the larger narrative. We will need to do this, because, as Wong tells us, to lose this history is death.

Join us for an author session with Elizabeth Wong in Lit Books on 6 Aug! Purchase tickets here.