by Elaine Lau

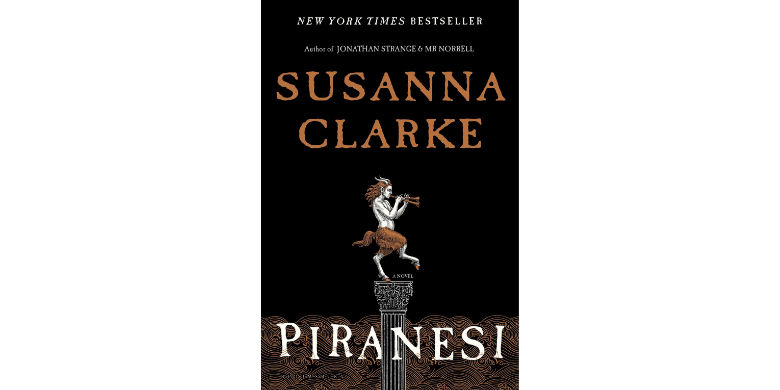

Susanna Clarke’s new novel, Piranesi, is a mystery. It is not, as the title might suggest, a novel about the 18th century Italian architectural artist famed for his etchings of Rome and atmospheric imaginary prisons. But his art must have served as inspiration for the British author, for in her novel we enter a dreamlike World that is at once beguiling and bewildering, haunting and enigmatic — much like the Italian master’s exquisite artworks.

This World is a decaying House with an innumerable number of marble halls like “an infinite series of classical buildings knitted together” and divided into three levels. The tides inhabit the Lower Halls, the Upper Halls are the “Domain of the Clouds”, whereas the Middle Halls are the “Domain of birds and of men”. Statues of varying sizes and composition inhabit every nook and cranny of this labyrinthine House. Outside, there is only the sun, moon and stars, and nothing else.

We know this from the journal entries of the novel’s titular character, Piranesi, although he tells us that is not his name. He regards the House with reverence and childlike wonder, and considers himself a “Beloved Child of the House”. Piranesi believes he is between 30 and 35 years old, and considers himself “a scientist and an explorer” who is determined to explore as much of the House as he can in his lifetime. He records every happening in his notebooks, be it tidal patterns or the behaviour of the rooks that come to nest, and catalogues the thousands of Statues.

Piranesi subsists on fish, seaweed and molluscs, and tends to the 13 skeletons in the House. Aside from biweekly visits from a figure called simply The Other — who is on a quest to uncover “a Great and Secret Knowledge hidden somewhere in the World” and needs his help — Piranesi lives a contented life of solitude.

One can draw parallels of his solitary existence with Clarke’s own experience of finding solace in confinement. For the past 15 years, the British author has been suffering from chronic fatigue syndrome, among other conditions, which has at times impeded her writing and caused her to withdraw from the world. In an interview with The New Yorker, she said that she would imagine herself in a place with “endless buildings but silent — I found that very calming”.

Clarke became a literary sensation with her 2004 debut novel, Jonathan Strange & Mr Norrell. This heady 800-page period fantasy tale of rivalling magicians set in sumptuously detailed 19th-century England won the 2005 Hugo Award, among other prizes, and sold more than four million copies worldwide. The novel firmly established Clarke’s narrative prowess and she was heralded as an exciting new literary voice to watch.

Which is why her second novel, Piranesi, published in September, was met with keen anticipation, especially more so because it has been 16 years since her debut. Piranesi is a very different animal from her debut — gone are the loquaciousness and helical plotline that made Jonathan Strange & Mr Norrell either an exhilarating or laborious read, depending on whom you ask. By contrast, Piranesi is a breezy 270-page novel of bite-size journal entries in straightforward language. But its deceptively simple form belies the story’s complexity and inventiveness. Clarke has crafted an evocative novel that explores alternate worlds, memory and the sense of self, madness and imagination, and the detrimental pursuits of the vainglorious.

Piranesi is a mystery, and true to form, the first 80 pages or so rendered me utterly mystified. But as with all well-constructed mysteries, it gets good, and it subverts all expectations.

Where things start to shift is when The Other tells Piranesi that someone is looking to infiltrate their labyrinth and means to cause harm, and he should not engage with this person, whom Piranesi dubs “16”. But of course, 16 does show up, and here is when the story turns into a puzzle-box mystery. We follow along with Piranesi as he slowly puts the pieces together and, in the process, uncover his real identity and past — and what a bombshell of a reveal it turns out to be.

But more than plot, Piranesi is an exquisite depiction of something primeval, namely man’s earliest attempts to make sense of our sublimely ordered universe. It comes as no surprise that the arrangement of Piranesi’s World is eerily reminiscent of ancient cosmology, whose ordering of the universe is perhaps more a reflection of the human psyche, in its attempt to impose a meaning to his wonderment and place in it.

This article first appeared on Oct 12, 2020 in The Edge Malaysia.