The man for which the Pulitzer Prize is named after, Joseph Pulitzer, led an inspiring life and left behind an enduring legacy. Born in Hungary on April 10, 1847, he made his way to American shores as a young man even though he barely knew any English (he was, however, fluent in German and French). While working odd jobs in the city of St. Louis, he taught himself English and the law, studying in the city’s Mercantile Library.

From these humble beginnings, he rose to become a stalwart in American journalism. He is described on Pulitzer.org as “the most skilful of newspaper publishers, a passionate crusader against dishonest government, a fierce, hawk-like competitor who did not shrink from sensationalism in circulation struggles, and a visionary who richly endowed his profession. His innovative New York World and St. Louis Post-Dispatch reshaped newspaper journalism. Pulitzer was the first to call for the training of journalists at the university level in a school of journalism. And certainly, the lasting influence of the Pulitzer Prizes on journalism, literature, music, and drama is to be attributed to his visionary acumen.”

When he wrote his will in 1904, he made provisions for the establishment of the Pulitzer Prizes to reward excellence in journalism and letters — in later years, drama and music were added as well. Specifically on literature, the Pulitzer website has this caveat: “The board has not been captive to popular inclinations. Many, if not most, of the honoured books have not been on bestseller lists.” Nevertheless, these books remain essential reading for any person who wishes to fully understand the canon of western literature.

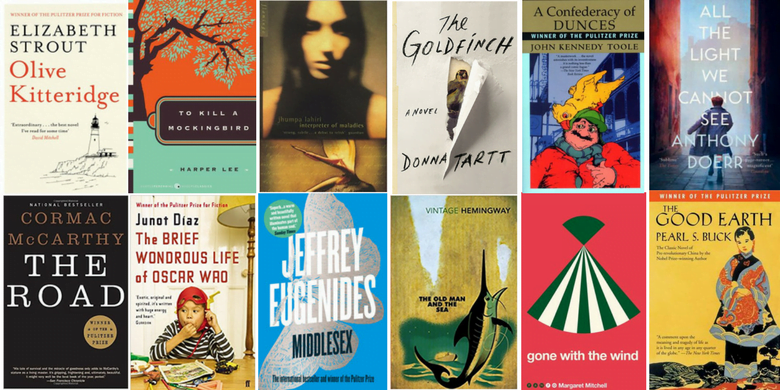

Following is the selection of Pulitzer Prize-winning novels available at Lit Books.

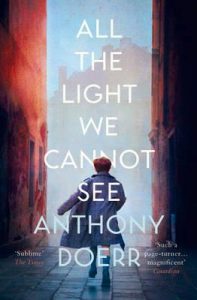

All the Light We Cannot See by Anthony Doerr

All the Light We Cannot See by Anthony Doerr

2015 Pulitzer Prize winner

Marie-Laure lives with her father in Paris near the Museum of Natural History, where he works as the master of its thousands of locks. When she is 6, Marie-Laure goes blind and her father builds a perfect miniature of their neighbourhood so she can memorise it by touch and navigate her way home. When she is 12, the Nazis occupy Paris and father and daughter flee to the walled citadel of Saint-Malo, where Marie-Laure’s reclusive great-uncle lives in a tall house by the sea. With them they carry what might be the museum’s most valuable and dangerous jewel.

In a mining town in Germany, the orphan Werner grows up with his younger sister, enchanted by a crude radio they find. Werner becomes an expert at building and fixing these crucial new instruments, a talent that wins him a place at a brutal academy for Hitler Youth, then a special assignment to track the resistance. More and more aware of the human cost of his intelligence, Werner travels through the heart of the war and, finally, into Saint-Malo, where his story and Marie-Laure’s converge.

Deftly interweaving the lives of Marie-Laure and Werner, Doerr illuminates the ways, against all odds, people try to be good to one another. Ten years in the writing, All the Light We Cannot See is a magnificent, deeply moving novel. (RM49.90)

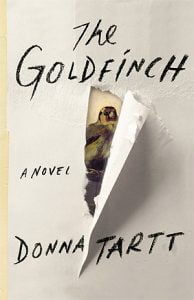

The Goldfinch by Donna Tartt

The Goldfinch by Donna Tartt

2014 Pulitzer Prize winner

A young boy in New York City, Theo Decker, miraculously survives an explosion that takes the life of his mother. Alone and determined to avoid being taken in by the city as an orphan, Theo scrambles between nights in friends’ apartments and on the city streets. He becomes entranced by the one thing that reminds him of his mother: a small, mysteriously captivating painting that soon draws Theo into the art underworld. Composed with the skills of a master, The Goldfinch is a haunted odyssey through present-day America. It is a story of loss and obsession, survival and self-invention, and the enormous power of art. (RM49.90)

Olive Kitteridge by Elizabeth Strout

Olive Kitteridge by Elizabeth Strout

2009 Pulitzer Prize winner

At times stern, at other times patient, at times perceptive, at other times in sad denial, Olive Kitteridge, a retired schoolteacher, deplores the changes in her little town of Crosby, Maine, and in the world at large, but she doesn’t always recognise the changes in those around her: a lounge musician haunted by a past romance; a former student who has lost the will to live; Olive’s own adult child, who feels tyrannized by her irrational sensitivities; and her husband, Henry, who finds his loyalty to his marriage both a blessing and a curse.

As the townspeople grapple with their problems, mild and dire, Olive is brought to a deeper understanding of herself and her life — sometimes painfully, but always with ruthless honesty. Olive Kitteridge offers profound insights into the human condition — its conflicts, its tragedies and joys, and the endurance it requires. (RM39.90)

The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao by Junot Diaz

The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao by Junot Diaz

2008 Pulitzer Prize winner

Things have never been easy for Oscar, a sweet but disastrously overweight, lovesick Dominican ghetto nerd. From his home in New Jersey, where he lives with his old-world mother and rebellious sister, Oscar dreams of becoming the Dominican J. R. R. Tolkien and, most of all, of finding love. But he may never get what he wants, thanks to the Fukú — the curse that has haunted the Oscar’s family for generations, dooming them to prison, torture, tragic accidents, and, above all, ill-starred love. Oscar, still waiting for his first kiss, is just its most recent victim.

Diaz immerses us in the tumultuous life of Oscar and the history of the family at large, rendering with genuine warmth and dazzling energy, humour, and insight the Dominican-American experience, and, ultimately, the endless human capacity to persevere in the face of heartbreak and loss. (RM35.50)

The Road by Cormac McCarthy

The Road by Cormac McCarthy

2007 Pulitzer Prize winner

A father and his son walk alone through burned America. Nothing moves in the ravaged landscape save the ash on the wind. It is cold enough to crack stones, and when the snow falls it is grey. The sky is dark. Their destination is the coast, although they don’t know what, if anything, awaits them there. They have nothing; just a pistol to defend themselves against the lawless bands that stalk the road, the clothes they are wearing, a cart of scavenged food — and each other.

The Road is the profoundly moving story of a journey. It boldly imagines a future in which no hope remains, but in which the father and his son, “each the other’s world entire”, are sustained by love. Awesome in the totality of its vision, it is an unflinching meditation on the worst and the best that we are capable of: ultimate destructiveness, desperate tenacity, and the tenderness that keeps two people alive in the face of total devastation. (RM75.50)

Middlesex by Jeffrey Eugenides

Middlesex by Jeffrey Eugenides

2003 Pulitzer Prize winner

In the spring of 1974, Calliope Stephanides, a student at a girls’ school in Grosse Pointe, finds herself drawn to a chain-smoking, strawberry blond classmate with a gift for acting. The passion that furtively develops between them — along with Callie’s failure to develop — leads Callie to suspect that she is not like other girls. In fact, she is not really a girl at all.

The explanation for this shocking state of affairs takes us out of suburbia- back before the Detroit race riots of 1967, before the rise of the Motor City and Prohibition, to 1922, when the Turks sacked Smyrna and Callie’s grandparents fled for their lives. Back to a tiny village in Asia Minor where two lovers, and one rare genetic mutation, set in motion the metamorphosis that will turn Callie into a being both mythical and perfectly real: a hermaphrodite.

Spanning eight decades — and one unusually awkward adolescence — Jeffrey Eugenides’ second novel is a grand, utterly original fable of crossed bloodlines, the intricacies of gender, and the deep, untidy promptings of desire. (RM49.90)

Interpreter of Maladies by Jhumpa Lahiri

Interpreter of Maladies by Jhumpa Lahiri

2000 Pulitzer Prize winner

Traveling from India to New England and back again, the stories in this extraordinary debut collection unerringly chart the emotional journeys of characters seeking love beyond the barriers of nations and generations. Imbued with the sensual details of Indian culture, they also speak with universal eloquence to everyone who has ever felt like a foreigner. Like the interpreter of the title story, Jhumpa Lahiri translates between the strict traditions of her ancestors and the baffling New World. Including two stories published in The New Yorker, Interpreter of Maladies introduces, in the words of Frederick Busch, “a writer with a steady, penetrating gaze. Lahiri honours the vastness and variousness of the world”. (RM39.90)

A Confederacy of Dunces by John Kennedy Toole

A Confederacy of Dunces by John Kennedy Toole

1981 Pulitzer Prize winner

After more than three decades, the peerless wit and indulgent absurdity of A Confederacy of Dunces continues to attract new readers. Though the manuscript was rejected by many publishers during Toole’s lifetime, his mother successfully published the book years after her son’s suicide, and it won the 1981 Pulitzer Prize for fiction. This literary underdog and comic masterpiece has sold more than two million copies in 23 languages.

The novel presents one of the most memorable protagonists in American literature, Ignatius J. Reilly, whom American author Walker Percy dubbed “slob extraordinaire, a mad Oliver Hardy, a fat Don Quixote, a perverse Thomas Aquinas rolled into one”. Set in New Orleans with a wild cast of characters including Ignatius and his mother; Miss Trixie, the octogenarian assistant accountant at Levi Pants; inept, wan Patrolman Mancuso; Darlene, the Bourbon Street stripper with a penchant for poultry; and Jones, the jivecat in space-age dark glasses, the novel serves as an outlandish but believable tribute to a city defined by its parade of eccentric denizens. (RM79.90)

To Kill A Mockingbird by Harper Lee

To Kill A Mockingbird by Harper Lee

1961 Pulitzer Prize winner

This classic has been voted the most life changing book by a female author.

A black man has been charged with the rape of a white girl. Through the young eyes of Scout and Jem Finch, Harper Lee explores with exuberant humour the irrationality of adult attitudes to race and class in the Deep South of the 30s. The conscience of a town steeped in prejudice, violence and hypocrisy is pricked by the stamina of one man’s struggle for justice. But the weight of history will only tolerate so much.

To Kill a Mockingbird is a coming-of-age story, an anti-racist novel, a historical drama of the Great Depression and a sublime example of the Southern writing tradition. (RM59.90)

The Old Man and the Sea by Ernest Hemingway

The Old Man and the Sea by Ernest Hemingway

1953 Pulitzer Prize winner

Told in language of great simplicity and power, this is the story of an old Cuban fisherman, down on his luck, and his supreme ordeal — a relentless, agonising battle with a giant marlin far out in the Gulf Stream. Here Hemingway recasts, in strikingly contemporary style, the classic theme of courage in the face of defeat, of personal triumph won from loss. (RM42.90)

Gone with the Wind by Margaret Mitchell

Gone with the Wind by Margaret Mitchell

1937 Pulitzer Prize winner

Widely considered The Great American Novel, and often remembered for its epic film version, Gone With the Wind explores the depth of human passions with an intensity as bold as its setting in the red hills of Georgia. A superb piece of storytelling, it vividly depicts the drama of the Civil War and Reconstruction.

A sweeping story of tangled passion and courage, it tells the tale of Scarlett O’Hara, the spoiled, manipulative daughter of a wealthy plantation owner, who arrives at young womanhood just in time to see the Civil War forever change her way of life.

Many novels have been written about the American Civil War and its aftermath. But none take us into the burning fields and cities of the American South as Gone With the Wind does, creating haunting scenes and thrilling portraits of characters so vivid that we remember their words and feel their fear and hunger for the rest of our lives. (RM49.90)

The Good Earth by Pearl S. Buck

The Good Earth by Pearl S. Buck

1932 Pulitzer Prize winner

When O-lan, a servant girl, marries the peasant Wang Lung, she toils tirelessly through four pregnancies for their family’s survival. Reward at first is meagre, but there is sustenance in the land — until the famine comes. Half-starved, the family joins thousands of peasants to beg on the city streets. It seems that all is lost, until O-lan’s desperate will to survive returns them home with undreamt of wealth. But they have betrayed the earth from which true wealth springs, and the family’s money breeds only mistrust, deception and heartbreak for the woman who had saved them. The Good Earth is a riveting family saga and story of female sacrifice — a classic of 20th century literature.

Nobel Prize winner Pearl S. Buck traces the whole cycle of life: its terrors, its passions, its ambitions and rewards. Her brilliant novel is a universal tale of an ordinary family caught in the tide of history. (RM44.90)

*The Pulitzer Prize winners for 2018 will be announced on April 16.

Super Sushi Ramen Express: One Family’s Journey Through the Belly of Japan by Michael Booth

Super Sushi Ramen Express: One Family’s Journey Through the Belly of Japan by Michael Booth A Year in Provence by Peter Mayle

A Year in Provence by Peter Mayle The Table Comes First by Adam Gopnik

The Table Comes First by Adam Gopnik The Whole Fromage: Adventures in the Delectable World of French Cheese by Kathe Lison

The Whole Fromage: Adventures in the Delectable World of French Cheese by Kathe Lison Salt: A World History by Mark Kurlansky

Salt: A World History by Mark Kurlansky Butter: A Rich History by Elaine Khosrova

Butter: A Rich History by Elaine Khosrova

All the Light We Cannot See by Anthony Doerr

All the Light We Cannot See by Anthony Doerr The Goldfinch by Donna Tartt

The Goldfinch by Donna Tartt Olive Kitteridge by Elizabeth Strout

Olive Kitteridge by Elizabeth Strout The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao by Junot Diaz

The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao by Junot Diaz The Road by Cormac McCarthy

The Road by Cormac McCarthy Middlesex by Jeffrey Eugenides

Middlesex by Jeffrey Eugenides Interpreter of Maladies by Jhumpa Lahiri

Interpreter of Maladies by Jhumpa Lahiri A Confederacy of Dunces by John Kennedy Toole

A Confederacy of Dunces by John Kennedy Toole To Kill A Mockingbird by Harper Lee

To Kill A Mockingbird by Harper Lee The Old Man and the Sea by Ernest Hemingway

The Old Man and the Sea by Ernest Hemingway Gone with the Wind by Margaret Mitchell

Gone with the Wind by Margaret Mitchell The Good Earth by Pearl S. Buck

The Good Earth by Pearl S. Buck