There are two schools of thought when it comes to business and management books: soulless instructional guides that reinforce the pragmatism of the pragmatic, and invaluable fonts of wisdom and information that will guide you to the upper echelons of corporate success. The truth, however, lies somewhere in the middle. Over the last few years, we have seen narrative nonfiction rivalling some of the best crime thriller novels out there, books on management technique that goes beyond looking for cheese, and leadership tomes that focus on more than just effective habits. These are some of our recommendations.

Why Should Anyone Be Led By You? by Rob Goffee and Gareth R. Jones (RM89.90)

First published in 2006, this new edition of an influential leadership text features a new preface by both Goffee and Jones on authentic leadership. They argue that leaders don’t become great simply by aspiring to a list of universal character traits; rather, effective leaders are authentic individuals who deploy individual strengths to engage followers’ hearts, minds, and souls. Authentic leaders are skillful at consistently being themselves, even as they alter their behaviour to respond effectively to changing contexts. In short, the authors present a powerful case: that it takes “being yourself, in context, with skill” to be a successful, authentic leader, and they show how to do that in this lively and practical book. Drawing from extensive research, Goffee and Jones reveal how aspiring leaders can hone and deploy their unique leadership assets while managing the inherent tensions of successful leadership.

The Wisdom of Finance by Mihir Desai (RM59.90)

Harvard Business School professor Mihir Desai in his “last lecture” to the graduating Harvard MBA class of 2015 took up the cause of restoring humanity to finance. With incisive wit and irony, his lecture drew upon a rich knowledge of literature, film, history, and philosophy to explain the inner workings of finance in a manner that has never been seen before. The mix of finance and the humanities creates unusual pairings: Jane Austen and Anthony Trollope are guides to risk management; Jeff Koons becomes an advocate of leverage; and Mel Brooks’s The Producers teaches us about fiduciary responsibility. In Desai’s vision, the principles of finance also provide answers to critical questions in our lives. Among many surprising parallels, bankruptcy teaches us how to react to failure, the lessons of mergers apply to marriages, and the Capital Asset Pricing Model demonstrates the true value of relationships. The Wisdom of Finance captures Desai’s lucid exploration of the ideas of finance as seen through the unusual prism of the humanities.

Bad Blood by John Carreyrou (RM69.90)

If nothing else, the sudden and unprecedented success of companies such as Facebook, Uber and Tesla have turned 21st-century investors into a frothing mob, hungry for the next big thing that will revolutionise the world and generate absurd returns. Accompanying this hunger is an unprecedented level of risk-taking, which in turn goes a long way to explain how Theranos, a Silicon Valley company promising to revolutionise the blood testing industry with its Edison machine, became the darling of some of the smartest and most influential investors in the world. The only problem was that the technology didn’t work. Theranos founder Elizabeth Holmes, once recognised as the youngest self-made billionaire by no less than Forbes magazine, now faces fraud charges that could send her 20 years behind bars. Author Carreyrou, an investigative journalist for the Wall Street Journal, wrote the first article in 2015 prompting authorities to open investigations into Theranos. Bad Blood, which reads like a thriller, provides additional details in what can only be described as the anatomy of a fraud.

The Fourth Industrial Revolution by Klaus Schwab (RM74.95)

The Fourth Industrial Revolution, or Industry 4.0, is a phrase that quietly snuck into the business lexicon over the last few years after the author, Klaus Schwab, announced its imminent arrival in a 2015 article. Characterised as a technological revolution, Industry 4.0 is shorthand for the what Schwab describes as a fusing of the physical, digital and biological worlds. Schwab outlines the key technological megatrends at the heart of the revolution and predicts major impacts on the way we govern, do business, organise society and behave as individuals. Industry 4.0 will impact all disciplines, economies and industries at an unprecedented rate with significant consequence for the management of business and policy-making. Prophetic and important.

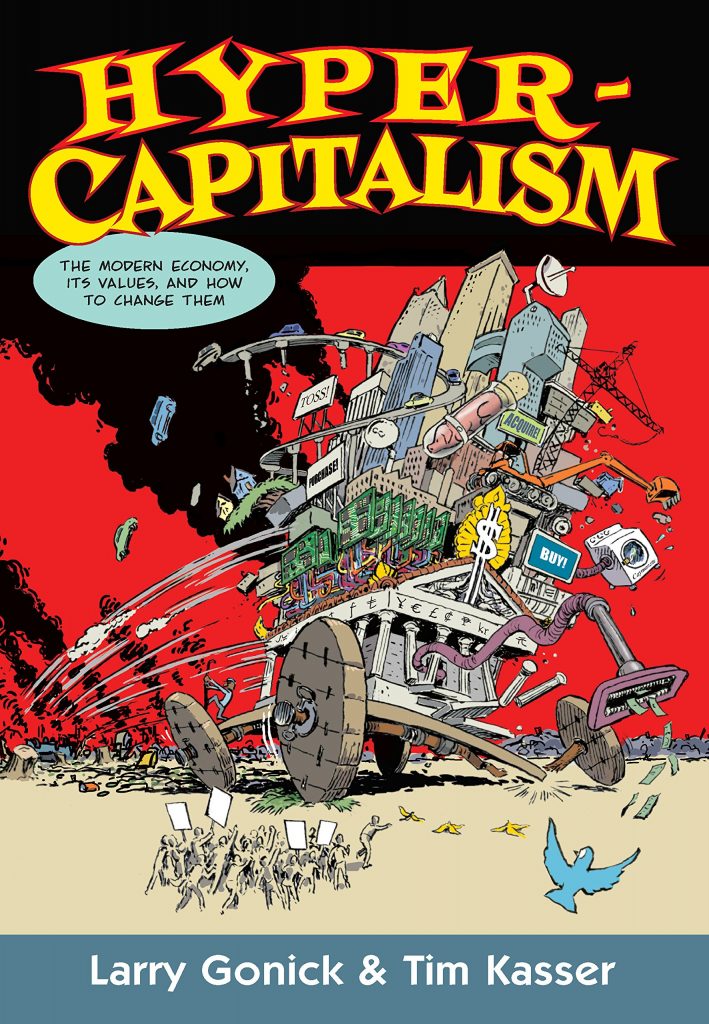

Hyper-Capitalism by Larry Gonick and Tim Kasser (RM69.90)

Google’s unofficial motto until 2018 was simply, “Don’t Be Evil” — it’s now a less eye-catching “Do the Right Thing”. Perhaps an acknowledgement that morality has no place in the business world, especially when a company is worth about US$750 billion, the move is an implicit nod to the maxim of business: leave right and wrong to the lawyers, but good and evil is a question for the philosophers. Hyper-Capitalism, a unique graphic novel exposing the roots of our modern economy, suggests that yes, there is good and evil in the business world, and no, we aren’t, on balance, on the good side of the equation. Drawing from contemporary research, Gonnick and Kasser describe and illustrate concepts (such as corporate power, free trade, privatisation, and deregulation) that are critical for understanding the world we live in, and movements (such as voluntary simplicity, sharing, alternatives to GDP, and protests) that have developed in response to the system. This book might not instruct you on how to become the top dog in your organisation, but it does reveal just how you might act in a slightly less evil way should you reach that point.

This article appears in the July 2019 issue of FireFlyz, the in-flight magazine of Firefly airlines.