The biography, rightly, stands as a sub-genre of its own within publishing and literary circles. At once a descriptive report as well as a work of psychoanalysis, the biography at its best digs deeply into the motivations and thinking of another person, replete with their biases, prejudices and preconceptions, to edify and illuminate thought processes. They are, therefore, windows into the minds of others providing explanation and justification for their actions in the tangible world. As a species, we have always been interested in the lives of others. Although no biography offers a complete perspective of the mental workings of another individual, they nevertheless, provide valuable insights into their hows and whys. The following titles are our picks.

Leonardo da Vinci by Walter Isaacson (RM59.95)

Walter Isaacson, the acclaimed biographer whose previous subjects include Albert Einstein, Benjamin Franklin, and Steve Jobs, adds to his list of geniuses who changed the world with his 2017 biography of Leonardo da Vinci. Now available in paperback, Isaacson masterfully weaves the maestro’s artistic and scientific life to reveal a man whose passion for one is intrinsically linked to the other. Drawing from thousands of pages from Leonardo’s notebooks and contemporary discoveries of his life and work, Isaacson’s portrait is one of a misfit fundamentally defined by his burning curiosity in the subjects of anatomy, engineering, art and theatre. This new work by Isaacson illuminates the importance of questioning received wisdom whilst keeping an open and imaginative mind as the key ingredients of creativity.

Serving the Servant: Remembering Kurt Cobain by Danny Goldberg (RM118.90)

Is 25 years long enough to determine if Cobain was a genius or not? Was Smells Like Teen Spirit an anthem for a generation of disaffected youth or simply the angst-ridden ejaculation of a bored cynic? Was he a genius or did he simply die young and popular? The debate over the legitimacy of Nirvana’s lead man continues to rage, but what is undeniable is his status as a cultural icon further cemented by the act of his suicide. Although Cobain is typically portrayed as a reluctant individual caught in the tailspin of his own rising star, Goldberg, Nirvana’s manager from 1991 to 1994, adds a new dimension to the story. In Serving the Servants, Goldberg draws on his own interaction with Cobain as well as on previously unreleased interviews to illuminate Cobain’s brilliance, compassion and ambition, and sheds new light on why Cobain endures till today.

Ernest Hemingway by Mary Dearborn (RM84.95)

Few writers are celebrated with as much bravado as machismo as Ernest Hemingway whose CV includes stints as a war-time ambulance driver and other intrigues, big game safari hunter, amateur boxer, inveterate drinker and womaniser, and writer. Even fewer bring the lessons and virtues (if they can be called virtues) from these preoccupations to bear on their writing, and far fewer can make something as beautiful and heart-wrenching as Hemingway does in his novels and short-stories. Mary Dearborn’s 2017 book is the first full biography of Ernest Hemingway in more than 15 years and the first to be written by a woman. Drawing on never-before-used material, Dearborn creates a rich and nuanced portrait of this enigmatic and flawed artist, who was driven and doomed by the insatiable demons that haunted him throughout his life.

The Pianist from Syria: A Memoir by Aeham Ahmad (RM75.50)

A memoir of a war-refugee who escapes from war-torn Syria to Germany, The Pianist is a contemporary account of the continuing and lingering impact of the conflict in the Middle East. Aeham Ahmad was born the son of a blind violinist and carpenter who taught him the piano and a love for music from an early age. A second-generation refugee — his grandparents and father were forced to flee Israel and seek refuge from the Israeli–Palestinian conflict — Aeham’s family built a life in Yarmouk, an unofficial camp to more than 160,000 Palestinian refugees in Damascus where family and music were their only haven. However, any plans to wait out the war in their new home would be disrupted by a new conflict in Syria, forcing Aeham to leave his family behind as he sought to find a new place for them to call home and build a better life. Told in a raw and poignant voice, The Pianist is a gripping portrait of one man’s search for sanctuary and of the bond between father and son.

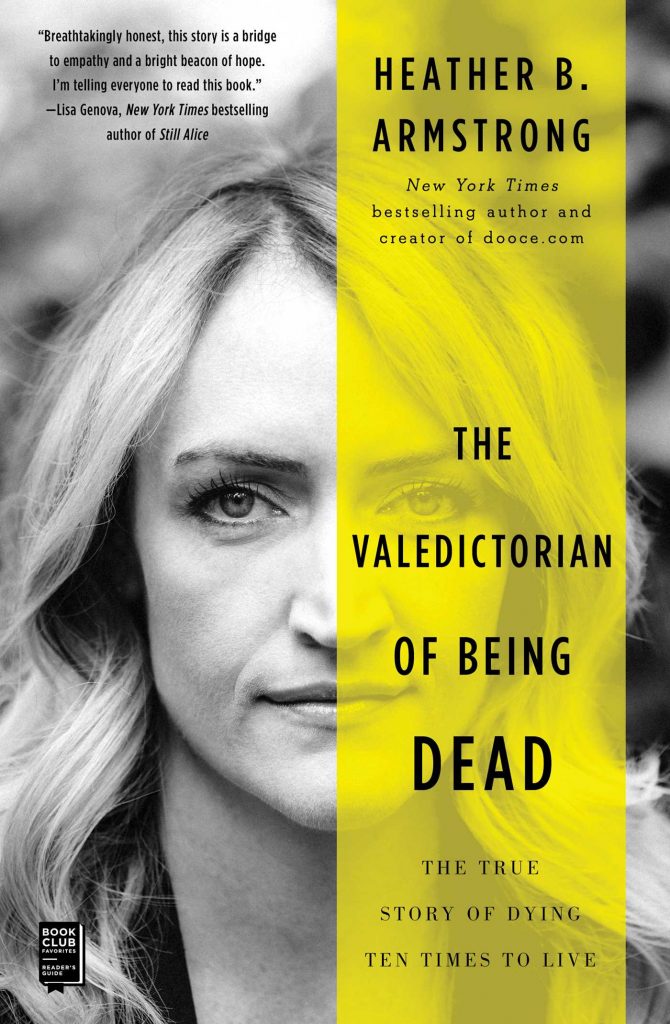

The Valedictorian of Being Dead by Heather Armstrong (RM89.90)

The Valedictorian is an honest and irreverent memoir by Heather B. Armstrong of her experience as one of only a few people to participate in an experimental treatment for depression involving 10 rounds of a chemically induced coma approximating brain death. Armstrong has struggled with depression for years, but when she hit rock bottom in 2016, she decided to risk everything by participating in the experimental clinical trial. In her memoir, she recalls the torturous 18 months of suicidal depression she endured and the month-long experimental study in which doctors used propofol anesthesia to quiet all brain activity for a full fifteen minutes before bringing her back from a flatline — effectively a brain reset. The experience was taxing for both Armstrong and her family, and seems to have worked since she has yet to experience an episode of suicidal depression since. Disarmingly honest, self-deprecating, and scientifically fascinating, The Valedictorian brings to light a groundbreaking new treatment for depression.

This article appears in the May 2019 issue of FireFlyz, the in-flight magazine of Firefly airlines.