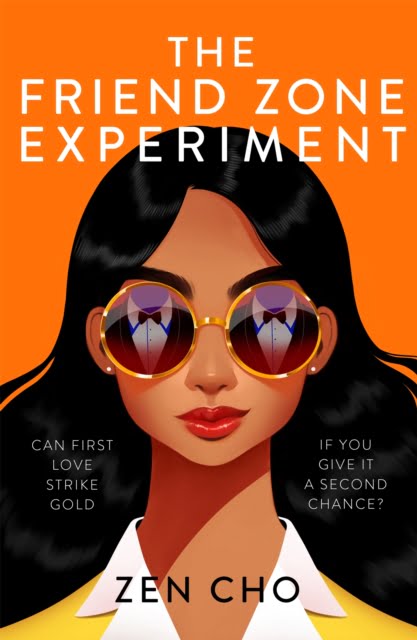

When it was first revealed that Zen Cho’s new book would be a contemporary romance, the news came as a surprise. After all, the UK-based Malaysian author has made a name for herself in the realms of fantasy and speculative fiction with such acclaimed titles as Black Water Sister and Spirits Abroad.

Zen’s new book is called The Friend Zone Experiment, and it’s inspired by K-dramas and political scandals. She says, “It’s a cross between the K-drama, Crash Landing on You, which is on Netflix, and like corporate intrigue and the 1MDB political scandal. It’s set in London about a young woman called Renee Goh, who is a Singaporean heiress who runs her own business. She’s estranged from her family, which is why she lives in London.

“But at the beginning of the book, she finds out that she’s in the running to take over her father’s company, which is one of these massive Southeast Asian conglomerates. And on the same day, she runs into her first love, Yap Ket Siong, who broke her heart 10 years ago when they were both at university and hadn’t been in touch since then. So they reconnect, but the secrets from their past and what they’re trying to achieve now threaten their renewed connection. That’s my elevator pitch for The Friend Zone Experiment.”

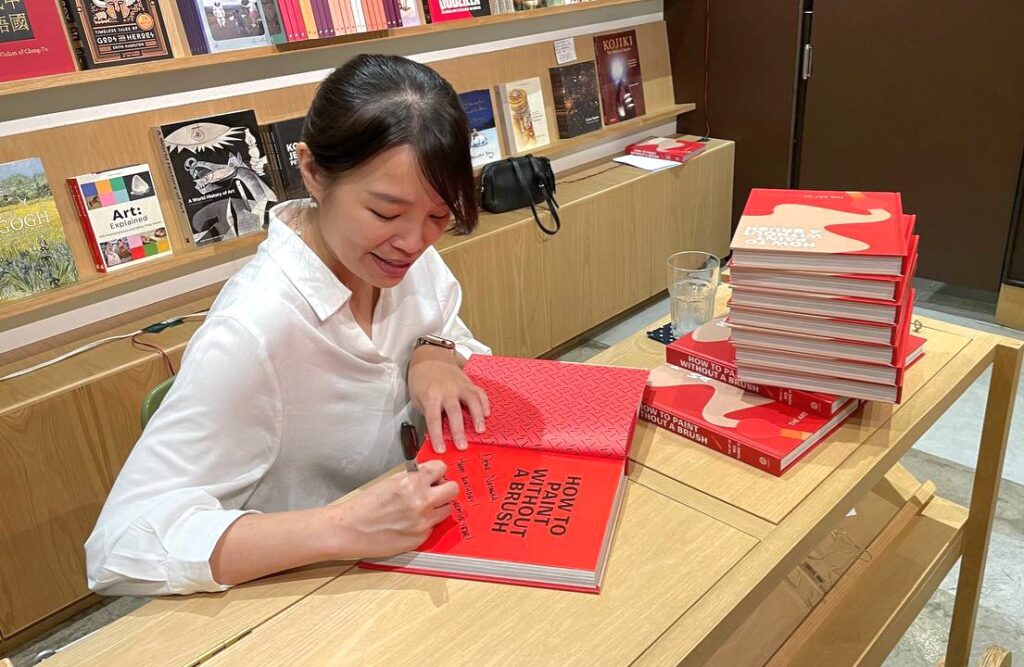

Zen was speaking to us at an author event at Lit Books on 17 Aug, 2024. She had initially wanted to go the self-publishing route because she wasn’t sure her agent would get behind this book. But her agent did see its potential and was supportive of it, even if she did caution Zen that genre-hopping might not be the wisest move commercially.

“This definitely is a departure for me. I definitely could have earned more money if I had stayed in fantasy,” she quips. “But I don’t actually write to make money because I could make money much easier if I just focused on my day job, which is being a lawyer. I was writing what I wanted to write.”

In the hour-long conversation that ensued, Zen spoke about how this all came about. Below are edited excerpts from the session moderated by our co-founder Fong Min Hun.

On why she enjoys K-dramas and how that led to writing The Friend Zone Experiment:

What happened was, during lockdown, I got really into K-dramas. What I really like, and I’m sure this will resonate with many of you who watch it, is that they really focus on very trope-led storytelling. It’s very entertaining storytelling; it’s often very over the top; it’s very light-hearted.

But then they also, at the same time, grapple with quite serious issues… Stuff like government corruption, family issues. That combination of the light-hearted and the substantive, I’ve always been really drawn to and tried to achieve in my work. So I said to myself, ‘Oh, I wonder what it would be like if I wrote my own K-drama.’ This is the result.

On incorporating Malaysian themes into the book, such as the 1MDB scandal and the issue of illegal logging:

In the earlier version of the book, it didn’t have anything to do with all that stuff. But my agent said it needed higher stakes; it needed more conflict. The male lead, Ket Siong, had a bereavement, and he was trying to work out what had happened. The female lead Renee always had a corporate succession subplot. And my agent was like, ‘Why don’t you make them scions of competing business families?’ Which, of course, is a very classic trope.

But it wasn’t quite what I wanted to do. And I think part of it was that their families are really important in the story and I wanted to tell a story where there were two very contrasting families. Renee’s from this wealthy family where it’s all about business and she’s in a competition against her brothers to try to become CEO of the family company. But on Ket Siong’s side, he’s actually from an activist family. His mom’s a lawyer who was very involved in civil society and so on. And that is going to be the thing that sets them on the path to clash, to be like a collision of values. And they have to decide what’s important to them.

I think that was where the Malaysian themes came in. What generally gives a story idea enough energy for it to become a novel for me is there’s a story I want to explore or understand. This was my chance to think about 1MDB.

On writing sex scenes:

I wouldn’t say I am very comfortable writing them, but they’re kind of mandatory for the genre. I mean, you can do clean romance as well, and I would say this is actually quite clean romance. But I did feel that there should be at least one sex scene.

But actually, what I enjoy writing much more are moments of intimacy that don’t necessarily extend to sex, but have a lot of meaning. I think this is from my Regency romance background because my first two novels, Sorcerer to the Crown and The True Queen, were inspired by Regency romance, by these kind of 1800s-style romances where even just the touch of the hands is very meaningful. And that’s something that has always spoken to me.

Something I like about K-dramas is there’s so much yearning in just looking at each other. For some reason, they always seem to stand at a distance from each other and stare at each other really meaningfully. And you’re like, ‘OK, this is quite awkward, but fine.’

Two of the scenes I’m proudest of in The Friend Zone Experiment that I enjoyed writing much more than the sex scenes is where the female lead, Renee, is cold, and the male lead puts his scarf on her. That’s a really meaningful moment for them both because they’re not really sure what terms they are on.

There’s another scene—this is not a spoiler because you know what happens at the end of romance novels—where they get together and he dries her hair after she’s had a shower. This caretaking scene has a quiet intimacy to it. That is what I was more interested in writing.

On writing within the confines of the romance genre:

A romance novel, for people who don’t know, has got a very specific definition. Firstly, the main plot has to be the development of the romantic relationship. The other thing is that it’s got to have a happy ending—either happily ever after or happily for now. I knew that I was going in with these kind of restrictions, as it were. But I really enjoyed it, actually. It was a fresh technical challenge.

With romance novels, there’s a formula, which I say in not a critical way at all. I found it quite interesting writing with those concerns and working within the boundaries but I didn’t let them really inhibit me.

But I did have some issues with my agent when we were editing the book. She pointed out that my style is very different from most romance novels where every emotion had to be expressed as a physical sensation. If the person was alarmed, their heart had to race. If they were nervous, you had to describe how sweaty their palms were. I gave in in a couple of instances, but I did push back on most of that because I feel that if you overuse it, it just doesn’t achieve what it’s intended to do, which is to evoke the same emotion in the reader. If you use it too many times, people’s eyes just skip over it, in my opinion.

On trying to market the book to publishers:

Most publishers turned it down. What was interesting was a lot of the feedback was, ‘Oh, the writing’s good, but it’s just a bit serious for where the contemporary romance market is at the moment.’

You can see this in fantasy and science fiction as well. I think after the pandemic and with all that’s happening in the news, people don’t really want to be stressed by their fiction. They’re looking for escapism; they’re looking for gentleness. And although I would say The Friend Zone Experiment is escapist, it does kind of have a strong vein of sadness in it. But I was lucky it did get picked up.

The Friend Zone Experiment is available at our store and online here.