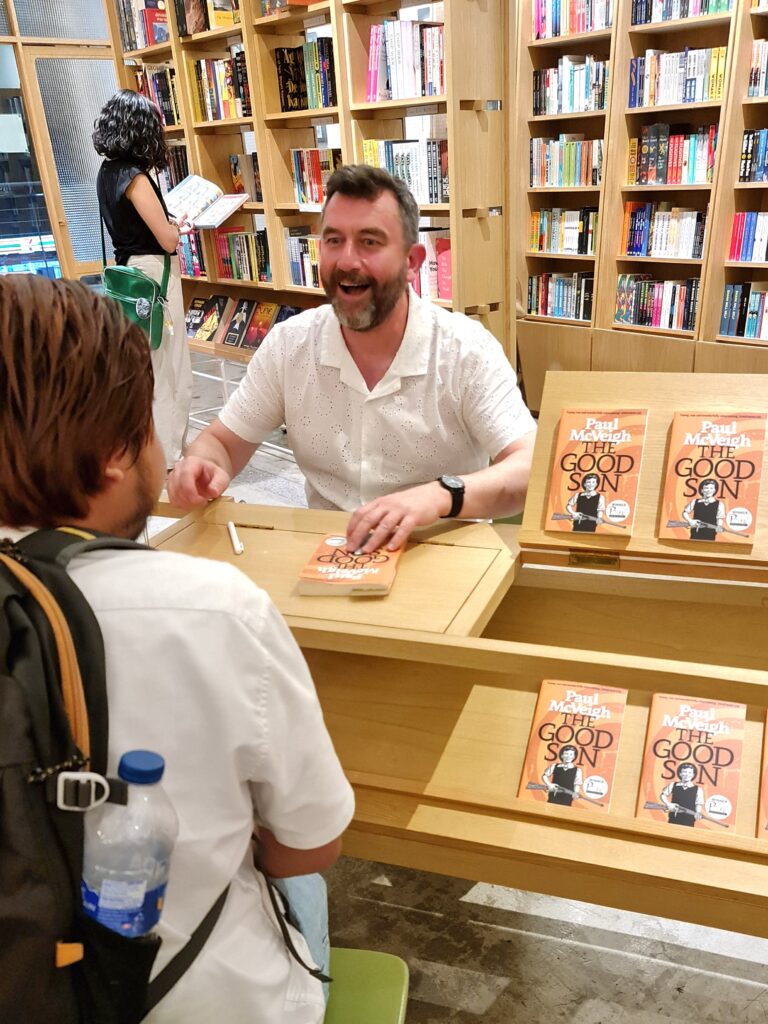

Malaysian writer Yeoh Jo-Ann burst onto the local literary scene when her debut novel, Impractical Uses of Cake, won the Epigram Fiction Prize in 2018. Together with Honey Ahmad and Diana Yeong of Two Book Nerds Talking, we spoke with Jo-Ann about her book over a Facebook Live session at the height of the lockdowns in 2020.

This year, we finally met in-person at a recent in-store event celebrating the publication of her second book, Deplorable Conversations with Cats and Other Distractions. The novel is about Lucky Lee who has everything—wealth, charm, good looks—but does little with it. He coasts through life and takes things for granted until his sister, Pearl, his only surviving family member, suddenly dies. As he struggles on without her, he begins to hear her cat talking to him.

Jo-Ann started writing Deplorable Conversations with Cats during the pandemic and worked on it during a three-month writer’s residency at the Kerouac Project in Orlando, Florida, US. She recalls, “I finished most of it but couldn’t end it. I didn’t know how… Then in January 2023, I somehow opened it up again. I read it and suddenly, it came to me. I knew how to end it and, within five days, the thing was done.”

She recounted this and more during the hour-long conversation with Lit Books’ co-founder Elaine Lau and our lovely audience on the evening of 27 April. The following are edited excerpts from the chat.

On where this novel comes from:

The book is about grief, but it’s also about sibling relationships and how difficult they are because they’re so complex. These are the people we grew up with, the people we know first, and the peers we know first. Your first betrayal and many other things was by a sibling, and they know you the way no one else does because they’re there right from the beginning.

I hadn’t really explored sibling relationships very much. When I talk to people about relationships, I find that I tend to have conversations about my relationship with my mother or whoever I’m dating at that time, stuff like that. But the sibling relationship tends to be something we don’t talk about very much, especially the strange, constantly shifting dynamic of someone who is a peer and yet not a peer, someone you didn’t choose. It’s that kind of encumbrance. But at the same time, if you need to be honest, it’s a sibling you can be completely honest with because they already know who you are.

So this is a book that explores grief and the many facets of it and how there are no right ways to grieve. It’s also about family and sibling relationships and how they can be beautiful and difficult and extremely frustrating. And somewhere in there is a talking cat because my mother is a cat woman of the first order, and I grew up having to play second fiddle to quite a few cats.

On grief and recognising how it changes a person:

We talk about how there are different ways to grieve and this is a thing that we all accept. I feel like we grapple less with how grief changes us and how we view the world and how we interact with people. When you think about dealing with grief, you think about coping mechanisms and things like that, but you don’t think about how grief really does change you. The process you go through when you’re dealing with loss and all of that, it affects you and it affects the people you interact with. That was what I was curious about also.

So in the novel, what I do try and grapple with is how Lucky is changed by losing his sister, grieving for her and not understanding exactly how to deal with it. It’s that kind of struggle that I was grappling with throughout the novel.

On creating the book’s main characters:

The main character of this novel is called Lucky Lee, right? He is handsome, he is rich, he is extremely privileged and therefore, a little unlikable. It’s not easy to identify with this rich man who has everything and doesn’t have to work. But I feel that grief is something that is not the privilege of the poor or rich. I wanted to explore having a character who was unlikable and yet you find yourself identifying with them somehow, even if I definitely didn’t want to.

On creating the wonderful cast of supporting characters:

The reason why the supporting cast for this one had to be so strong was because Lucky is really an irritating little thing. There are only so many ways that you can spell out that someone is irritating and irresponsible and hasn’t got ambition. What I did was to have the people around him communicate that through their experiences with him and the daily frustrations that they have to put up with because he is the man that he is. So it’s the effects of Lucky’s character that you see throughout the book, all the consequences of the actions that he hadn’t thought through or hadn’t bothered very much with or things that he was supposed to do but didn’t. You experience Lucky through them more than him doing things.

On how a talking cat came into the picture:

I’ve always wanted animals to be able to talk back to me, because I cannot resist speaking to animals when I see them.

I always wonder where cats go. Being from a household where I am a second-class citizen, I do wonder where the more superior beings go off to when they’re not at home terrorizing me. I often wondered if there was a parallel society of some sort. Do they congregate? What do they talk about? Do they talk about us? Is there a plot to overthrow mankind?

So, I guess that part of the book where the cat walks off and meets the Raja Kuching and all the cats help her and do things, that’s my imagination running a little wild.

On incorporating food into the narrative:

My experience in my family is that it’s easier to talk when your hands are occupied, when you’re eating or cooking, or when you’re preparing stuff like chopping chili padi—it’s easier to talk to your mother about things.

I think that’s what worked its way into the first novel and the second one, because I feel that it’s a vehicle for us when it comes to expressing ourselves. In the novel, what you’ll find is that a lot of the difficult conversations between Lucky and Pearl or when they’re fond of each other is when they’re helping each other out in the kitchen or fighting over something in the kitchen. But they spend a lot of their time in the kitchen doing things together, and that’s where all the family drama happens.

I am also very food motivated, like most cats. In order for me to sometimes write a chapter, I must know what I get to eat after I finish the chapter.

Deplorable Conversations with Cats and Other Distractions is available in-store and online.