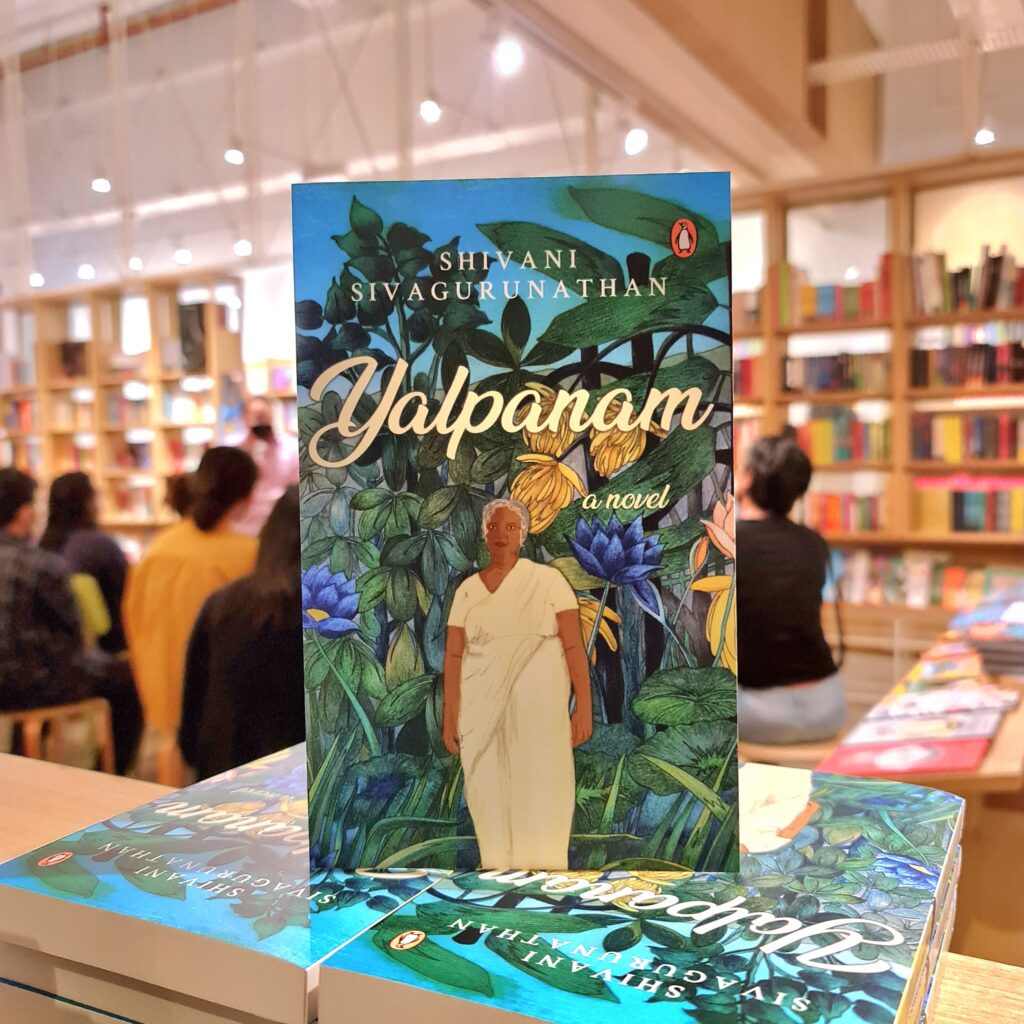

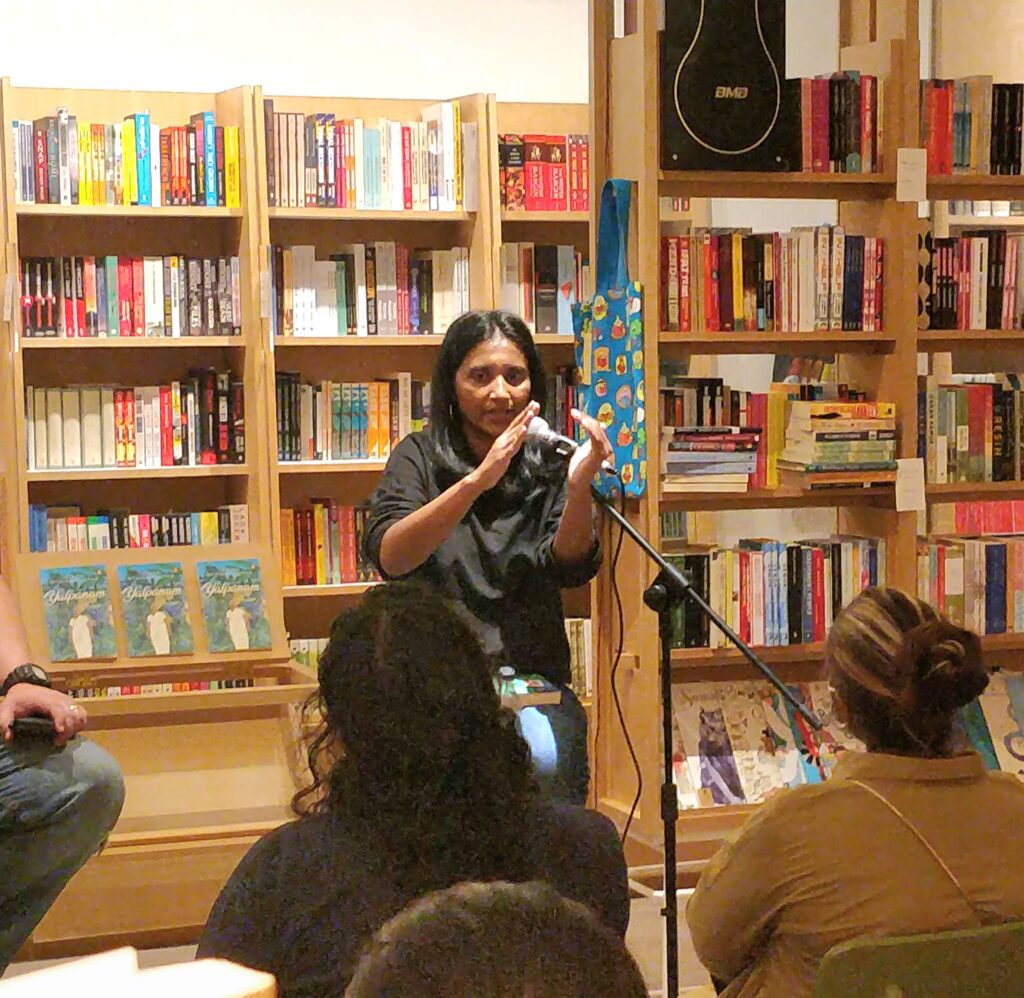

After a two-year hiatus due to the pandemic, we hosted our first in-person, in-store literary event on Saturday, 4 June, 2022. The occasion was to fete Malaysian author Shivani Sivagurunathan and her first full-length novel, Yalpanam, published by Penguin SEA last year. The novel is about the unlikely friendship of 185-year-old Pushpanayagi and her 18-year-old neighbour, Maxim Cheah, and how both would have to revisit the past in order to become whole persons and move forward in their lives.

Shivani, who is assistant professor in English and creative writing at the University of Nottingham Malaysia, spoke with Lit Books owner Fong Min Hun about the long journey it took to write her first full-length novel and the intricacies of the story and characters. Excerpts from the conversation is reproduced below.

Min Hun: How did you come to write this particular story and how long did it take you to write it?

Shivani: It was a very convoluted journey because I started writing it in 2011 just after my first book was published, Wildlife on Coal Island, which is a collection of short stories. I was on a writing spree basically; something was unlocked within me. The first image that appeared with regards to this book was of Pushpanayagi herself. What I saw was a really fat old woman in a white saree doing a bit of gardening. It was a very compelling image. I saw that the garden was very fertile, almost Edenic, and at a slight distance was an old colonial-style house.

That was a very magnetic image that I started to follow and basically, image followed image followed image, and then a story was unfolding. The first half of the novel, right up to the point where Maxim moves into yalpanam, would flow beautifully. It was very engaging; I was really getting into the mood of writing. I felt very much in control. When I reached the middle point of the novel, things would just fall apart. I would be lost; it drove me mad. From 2011 to 2014 I was writing and rewriting this novel.

This book went through so many changes and finally in 2014, I put it away. I thought fiction writing isn’t for me; I’ll just go back to poetry. In retrospect I see that what had to happen was I had to grow up as a person and as a writer in order to complete this book. I put it aside, got a job teaching creative writing at the University of Nottingham Malaysia and frankly, that was the training I needed.

In 2018, I managed to score myself a sabbatical. I got six months off work to do something. Initially I was not planning to go back to this novel… I had a novella written in 2014 so I thought to return to that novella and work on that. But a writer friend of mine took me away to Tioman and encouraged me to go back to the novel. Very interestingly I realised that the distance, the time spent away from the manuscript, really helped me to see it more clearly. I could read it more objectively; I could see where it was problematic. I basically rewrote it.

MH: How autobiographical is this book?

S: I’d say that all fiction is autobiographical; it’s just a question of how [much so]. This novel is not very overtly autobiographical but I definitely did draw on my complex relationship with my Sri-Lankan-Tamil heritage, exploring the complex relationship one can have with one’s own inheritances in terms of the question of displacement and the pain of feeling severed from one’s own culture.

MH: It’s a challenging book to read, Shivani, but at the same time rewarding. I find with a lot of difficult literature, if you persist with it, while there may be parts that you don’t fully understand, you find yourself rewarded by it at the end. Your book was one of those. There were two or three different timelines going on at the same time and at the start, I think you deliberately try to confuse your reader. For example in the book, you talk about the rupturing of the notions of reality and when I read that I thought to myself, ‘This is what Shivani is doing. She is trying to shake me out of this comfort zone from the very start of the book.’ Was that what you were trying to do?

S: Absolutely. I’m really glad that you experienced that. When the novel starts, we see Pushpanayagi, who’s basically been a recluse for close to seven decades. She lives in this house on her own, and the only person she meets is Hadi the vegetable seller who comes to her house to collect the vegetables that she grows; that’s how she earns a living. She’s been living in a state of stagnation for seven decades and she has a very myopic vision of reality, of the world, and of herself. The way she lives life is a very narrow way of living. The process of transformation that she goes through is a process of dismantling these fossilisations, a rupturing of this perception of reality that has basically kept her in a kind of paralysis.

Similarly, with Maxim — she’s been brought up in this very sheltered home, she’s been fed on a diet of certain beliefs and ideas that are very limiting. The journey that they’re both on is one of dismantling these encrustations and that necessitates a questioning of what they’ve been believing, a questioning of assumptions, and then seeing what else is there. It’s problematising reality, problematising what is. It’s saying that reality is so much bigger and so much more complex than we think it is. There are multiple versions, multiple perspectives. It’s sort of asking the reader also to consider what you’ve been taking for granted and saying let’s open up the world.

MH: Maxim wasn’t particularly enigmatic but I couldn’t figure her out. Why was she so hurt by her family’s circumstances that she felt the need to run away? Tell me more about Maxim and how she fits into this picture.

S: Maxim is, you’re right, not a very enigmatic character. She’s also very young. There is a big contrast between someone who is 185 years old and an 18-year-old who is particularly emotionally immature. She’s a deeply lonely person. She’s friendless. She hasn’t really had that kind of training in looking at her emotions, at her interior world, and being able to process it and understand what’s going on. In terms of her response to her situation, I think it’s fitting for the kind of person that she is.

MH: There is something very broken about Maxim, or something fundamentally missing in her and we do get that part of the story later on when she tries to uncover her own secret history. You were talking about how reality is not all that it seems to be and there is something about reclaiming history and the past for an alternate future. So, this is a book about secret histories, isn’t it?

S: To some extent, yes, the unearthing of stories that have not been heard before, the stories, the voices, the experiences and feelings that have been repressed that have been banished to some kind of psychical outer space that need to be aired in order for us to get a fuller perception of reality. What does it mean to open up reality? It is to bring in these perspectives that haven’t been seen before. In that sense, yes, there is a lot of secret histories that are coming to the surface.

MH: There does seem to be a lot of writing with a preoccupation with secret histories, or an attempt to try to flesh out the world as we know it through knowledge that was once known but perhaps now hidden or now lost. I’m wondering, why do you think there is this current in contemporary writing? Is it because we are somehow dissatisfied with who we are today? Is modernity so sterile and so limiting that we want to recover something about ourselves that we no longer have?

S: That’s a great question. I think it comes, yes, from our dissatisfaction with who and what we are now because we feel lost in terms of our identity. Maybe we don’t feel like we’re grounded enough or that we understand where we are. What do you do if you you’ve lost your way? You can’t move forward without going back. There’s always something that occurred in the past that hasn’t been resolved, accepted or processed, that hasn’t been truly grasped. And so, we have to keep returning to the past in order to really understand where we are now.

MH: There are two very distinct voices throughout the book. One voice is very poetic, uses a lot of imagery and allegory. The other one is more straightforward prose. Was this tension between these two voices deliberate?

S: Yes, in a very practical sense because there are actually three narrators in the novel. There’s Pushpanayagi’s point of view, there’s Maxim’s point of view, and then there’s a third unnamed narrator…. the grandiose, philosophical, poetic voice. I had to make sure that the language Maxim uses and the language that Pushpanayagi uses were authentic to the kind of people that they are. Maxim would never speak in very poetic, grandiose ways. For Pushpanayagi, in the initial stages of writing her, her voice did come out very poetic, but then as I clarified her voice, I realised that it wasn’t actually that philosophical or that dense. Then I realised that there was still space for a lyrical, philosophical voice, hence, the third narrator. I have a very clear idea of who or what that narrator is and it’s sort of related to the core of the story, which is asking metaphysical questions.

Yalpanam is available here.