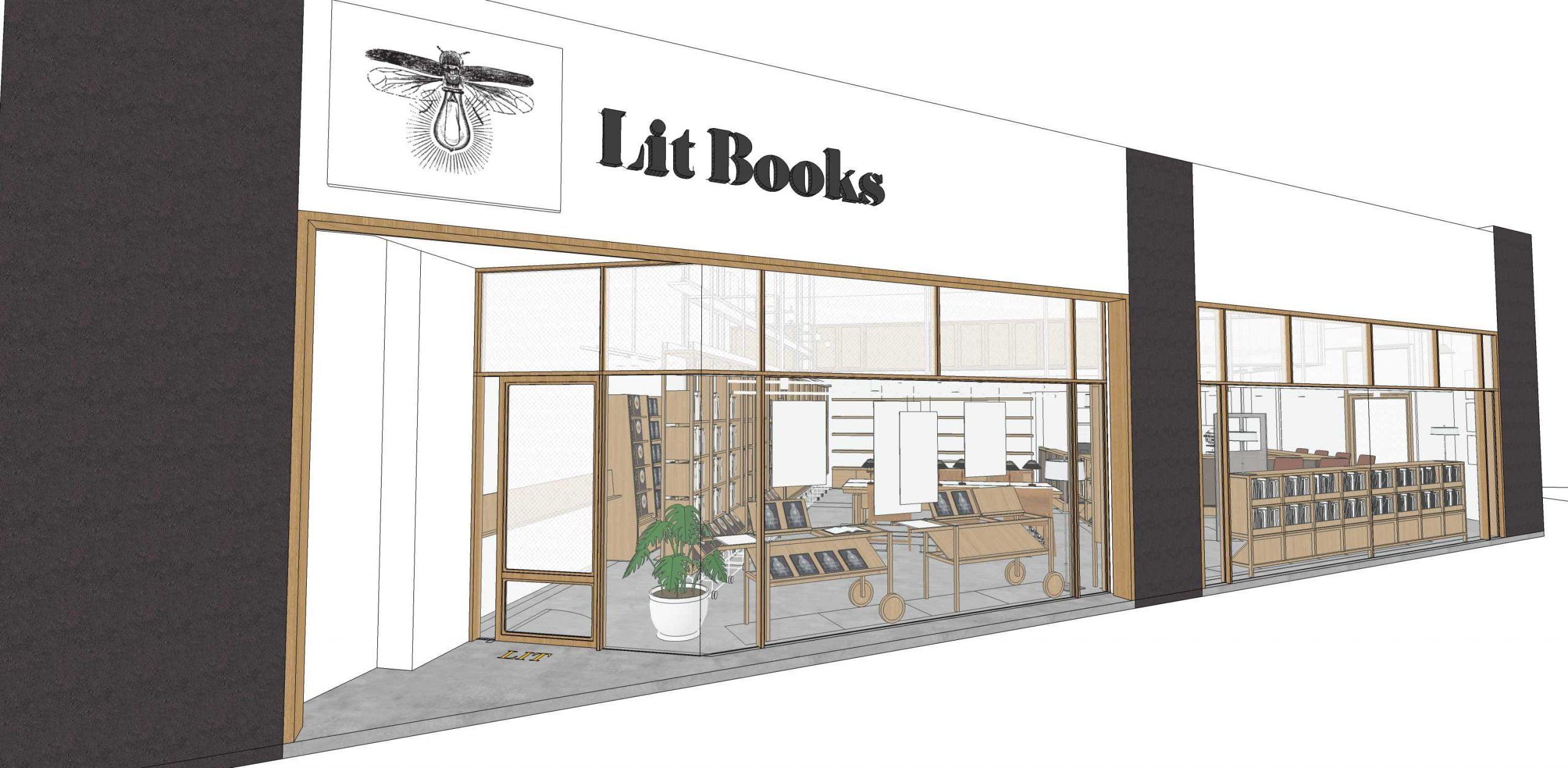

On an almost daily basis, someone will come into the shop to ask us one of these questions or a permutation thereof.

‘How are you different from other bookshops?’

‘What’s your concept?’

‘Are you a library?’

We run through the usual answers:

- As an independent bookstore, we personally select the books we have;

- Yes, you can find some of our titles in other bookshops;

- We are a bookshop with a cafe attached that serves drinks;

- No, we don’t lend out books but we don’t mind if you pull a book from the shelf to read while you’re enjoying a cup of coffee (just be careful with them!).

While we understand that bookshops such as ours aren’t ubiquitous these days, it bemuses me slightly that people think that our concept is original. Bemusing not because I think that our customers are yokels, but because bookshops, at least for some segments of our society, have become a forgotten cultural artefact.

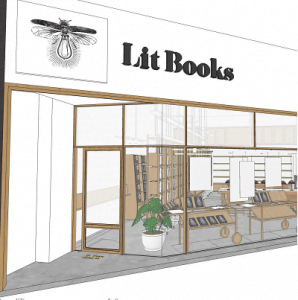

Don’t get me wrong — we appreciate and are grateful for all customers who walk through our doors, but the fact remains that Lit Books isn’t, and shouldn’t be, a cultural phenom. It might help, therefore, for us to describe what we are trying to do in the grand scheme of things by explaining some of what we do do in our shop.

Why do you have titles that we can’t find elsewhere in other bookstores?

For a very simple reason: because these are books that we (Elaine and I) like that we think other people might like as well. We believe that the character of bookstores, particularly an independent bookstore, is very much represented by the titles that they choose to stock (and by corollary, the titles that they choose not to stock). We don’t have a central buyer as chain bookshops do, and our selection of new books and authors is based on research and gut instinct. (This is why we stock both The Pillow Book of Sei Shonagon and Heath Robinson’s How to be a Perfect Husband. No prizes for guessing who picked which title!)Do you get your books from local suppliers?

Yes! In fact, we get the vast majority of our books from local suppliers just like everyone else. So why do our titles differ? It has to do with the way the book business is conducted where distribution rights from publishers are assigned to local distributors. However, by ordering books from the publishers’ catalogues rather than the distributors’ catalogues, we can establish our own identity by choosing books from a larger pool.Why are you more expensive than XXX?

Lit Books adheres strictly to the recommended retail price (RRP). Every book comes with an RRP which becomes the official price of the book. Retail booksellers get a discount from wholesalers, and this discount then becomes the profit margin for the retailers. The discount that retailers get from wholesalers vary based on various factors. One of the major ones is the purchase volume. Simply put, if someone were to buy 1,000 copies of a book from you, you would be more likely to give them a greater discount than someone who only buys four or five copies. The retailer who purchases 1,000 copies can then pass the savings on to their customers. I’m one of those guys who buys four or five copies of a book.Why don’t you buy more copies to enjoy greater discounts?

Mainly because as an independent bookshop, we don’t have very deep pockets. While we could opt to blow our entire budget on the next bestseller, that’s not really what we’re about.So what are you about?

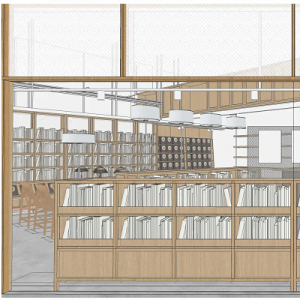

We want to create a bookshop that encourages people to browse and explore new authors and titles. Our target audience, to be perfectly frank, is the reader who knows they’d love a book to read but not entirely sure what it is that they want. I’d love for someone to come to my store looking for the latest Jodi Picoult only to walk away with Joan Didion’s The Year of Magical Thinking. Or for someone who’s looking for the new Jack Ma biography to walk out with Siddhartha Mukherjee’s Emperor of All Maladies. This is not to say that the books that they’re looking for aren’t great, but rather that we want to provide alternatives: we want to be the path less taken.Can we order a coffee, sit and read a book?

Yes! In fact, we encourage our readers to grab a few books, sit down and try them out to see if they fit before they decide on making a purchase. But please bear in mind that we are a mom-and-pop, and a damaged book is not a saleable book. We can’t return the book to our distributors and any damaged book directly impacts our bottomline. I don’t want to be that guy who goes around telling people not to dog-ear our books, or crease the spine, or flip the pages with greasy fingers — we are all adults and should be aware of what passes as good book-reading etiquette. We will never shrink wrap our books (except for the super-premium ones) and if you do find some still bound in plastic, it’s probably because I was too lazy to take it off myself.Why don’t you shrink wrap your books?

Because books need to breathe. But seriously, it’s because we’d hate to sell a book to someone who hasn’t had a chance to try it out. Book buying is not that different from starting a relationship, and you wouldn’t want your potential spouse shrink wrapped and shipped to you in a box.Do you recommend books?

Boy, do we ever! Please harass, harangue and kacau us about helping you find the right book. If I’m outside having a smoke, tick me off and drag me back into the shop. We love talking about books and we learn as much as you do during the exchange.

So that’s it, really. I hope this gives you a rough idea of what we’re trying to do. This post didn’t start out with the intention of becoming an FAQ and I had some Serious Ideas about curation I wanted to share. That will have to wait till next time. If you have any questions — any questions at all — left unanswered, please post them in the comments below and I’ll try to address them as best I can.