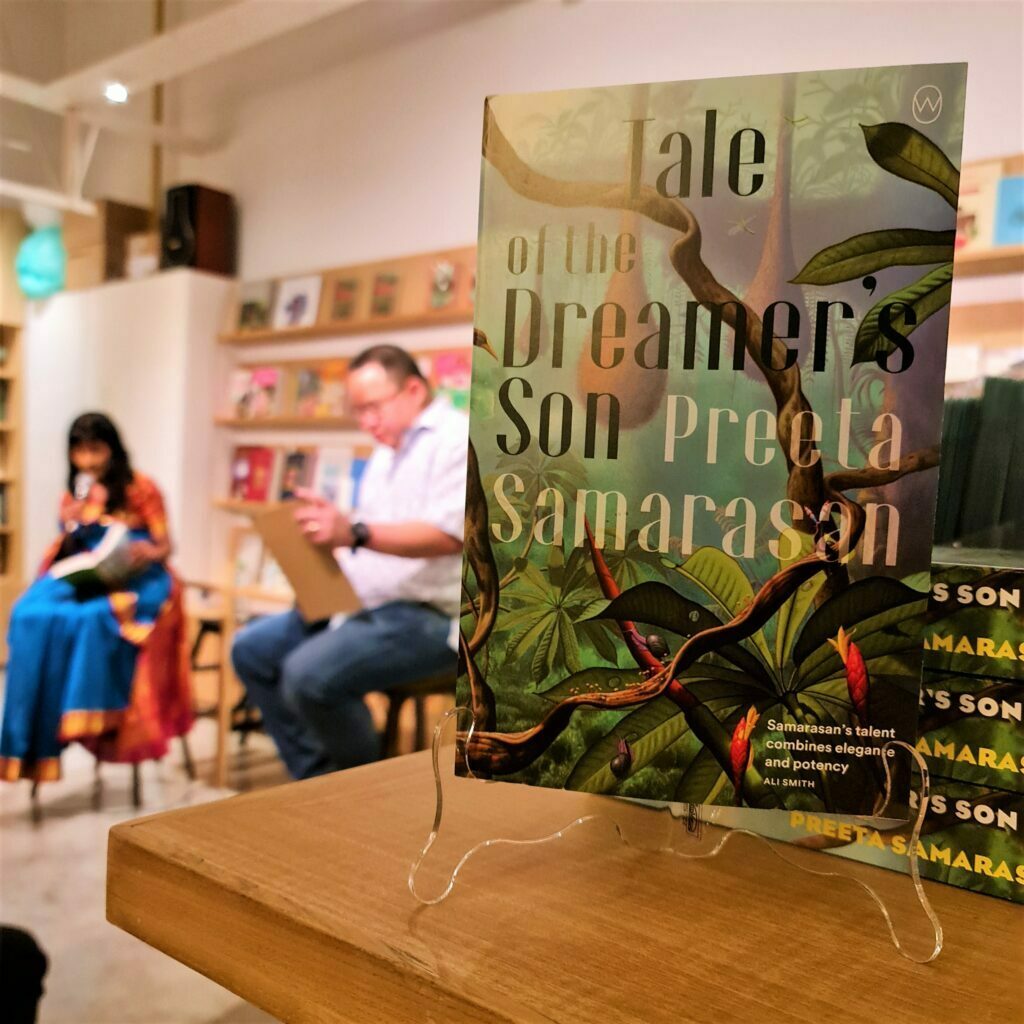

Fourteen years after her critically acclaimed debut novel Evening is the Whole Day was published, Preeta Samarasan returns with her second full-length novel, Tale of the Dreamer’s Son. It is an ambitious and darkly humorous book that examines the hubris and frailties of a community of Malaysians. Novel and insightfully written in a way that only Preeta can, the book delves into the synthesis of religion, politics and violence that lies at the heart of this country.

The France-based Malaysian writer celebrated her homecoming and launch of the new novel at Lit Books on 5 Nov, 2022. Below are edited excerpts from the conversation she had with Min Hun.

On how the novel first took shape:

This book very much began with the characters, with their individual stories. […] It’s about the children, first and foremost, who are just dragged along their parents’ weird, spiritual quest. It’s, of course, also about the way that the Malaysian political context shapes the destinies of the characters, in a quite obvious way.

I began with the child, the narrator Clarence Kannan Cheng-Ho Muhammad Yusuf Dragon. I started with him because I have been very interested in the way that parents decide what values their children are going to believe, the values that they’re going to pass on. I think this is true for all children but it’s sort of more apparent when the parents embark on some unusual spiritual journey.

I tend to not begin with themes. Everything grew out of this idea of who would this child be, what would it be like to be an observant child yet a child sort of marooned in this weird situation where your parents, they have this weird relationship to the cause. And you’re there trying to figure it out. I did have this novel be bookended by May 13th and Operasi Lalang, and I think the themes emerged out of that as well.

On whether the novel is the story of Malaysia writ small:

It is this one guy who’s a visionary trying to build what he feels he can build… Yes, Malaysia writ small. He’s building a small community where all of what he wants Malaysia to be can be done in this hermetically-sealed context. He’s lost hope that it can happen on the grand scale, but he can at least do this.

On how she came up with name and concept for the Muhibbah Centre for World Peace in the book:

It went through several iterations. I had various, different names, and none of them felt right. And then one day, we were discussing the whole concept of muhibbah on social media and I was like, ‘That’s it!’ That’s the Orwellian concept this book needs … you know, this big hope but it ultimately means nothing. It’s empty. It doesn’t ever happen.

It’s not based on any one particular sect or cult. My parents, they never entered into any residential commune like this where they were fully involved in the cause, but they experimented in a lot of different things. My mom especially was always seeking truth. As a child I was exposed to a lot of religious movements and the characters are amalgamations of people that I ran into and also of the infighting that I saw in all of these movements. And also, the way that I was exposed pretty young to different religious leaders and the way they’re all this sort of weird mix of really believing in the cause, being really committed to their values but also being flawed human beings, having their own desires and imperfections.

On whether May 13th continues to be a major issue in Malaysia:

I think on a conscious level, no. I think most people don’t think about it, really. It’s sort of gone. But I think that, the fact that people don’t think about it is the exactly why it continues to matter. Because I think we’re not really exorcising those ghosts; we’re not really facing our history and not really talking about why and how we would want to depart from where we were. Precisely because we don’t talk about it in any meaningful way, it’s still very much a part of our biological makeup as a nation.

On whether her role as a fiction writer is about seeking redemption:

I feel like that’s kind of what almost all writers do. We tell these stories in an effort to somehow fix something in the retelling, even if the retelling is not in an obvious way because it’s not like we retell the story and then put some happily-ever-after perfect ending. But somehow in the retelling, it’s a way to relive it and to fix certain things. I think this is an idea that was there in my first novel and it’s very much there in Ian McEwan’s Atonement. It’s in a lot of books, this idea of going back into history and somehow if you can think about it the right way, if you can just fix the story in your head, that you’ll change something, that you could change the way that we experience the present.

On her favourite character in the book:

Oof. They really aren’t likeable characters. They each have their moments where they’re actually being kind of a halfway decent human being. I have a lot of sympathy for the narrator, especially when he is a child. But would I want to be his friend? No, absolutely not. He’s terrible. I mean, I wouldn’t want to spend more than two hours with him. When he’s a child, he’s my favourite character in the book. He has the possibility of becoming what he doesn’t become.

On portraying identity and class in the novel:

I think it would’ve seemed too unrealistic to have everyone treating everyone, regardless of race or class, with the utmost respect all of a sudden. You can’t just switch on a switch and all of a sudden Malaysians, or anyone anywhere in the world, becomes capable of never thinking about class or race. Of course, they arrive at this community and the idea is that they’re never supposed to think about race and class. But they just can’t do it. In the end, they’re just conditioned by their prior lives. I’m not trying to make any larger point but as a writer, I felt myself constrained by reality. Like how would Malaysians behave if they suddenly found themselves in a place where they can’t talk about race? I don’t think they could do it.

On how different the experience of writing this second novel was from the first:

It was quite different, for one because Evening Is A Whole Day is so much closer to my immediate life experience. It was about a Malaysian Tamil family. It wasn’t autobiographical, but it drew a lot on my familiar world. In this one, I had to, sort of, invent a lot more, speculate a lot more, imagine a lot more. So the experience of writing it was very different. The experience of publishing it was night and day. […] It’s not a book that’s easy to pigeonhole ethnically and because it’s a much less South Asian but much more Southeast Asian book, it’s much, much harder to sell because Southeast Asia is unfamiliar to the West. And the West is not particularly interested in Southeast Asia yet. They say they are, but they’re not really. So yeah, it was very different in that sense as well.

Check out Tale of the Dreamer’s Son here.