Malaysian writer Vanessa Chan had always dabbled in writing fiction. But it took what she called a “millennial existential crisis” to propel her to pursue it seriously—she left her job in communications at Facebook and enrolled in a writing graduate programme in New York City.

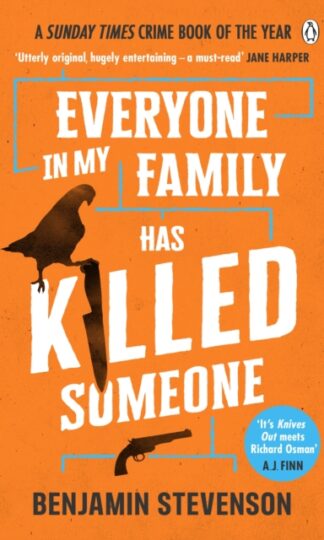

What then started out as a short story assignment for class where Vanessa wrote about a teenage girl going through checkpoints during the Japanese occupation of Malaya in World War II eventually turned into her debut novel, The Storm We Made, published in January 2024. The novel is about a housewife, Cecily, and how her decision to collaborate with the Japanese occupiers brought about political and personal devastation for the nation and her family, in particular her three children, Jujube, Abel, and Jasmine.

Vanessa recalls the moment she had a novel in the making: “I got a handwritten note from my professor, and it said, ‘This is actually not a short story… This is actually something more. All the air left the room when I read it, and my breath caught in my throat. There’s something I want you to protect. I think this is an outline or your brain telling you that this might be the beginning of your life’s work.”

But Vanessa didn’t think she would write historical fiction. “I always thought I would write like a millennial angst novel about a girl doing millennial things. But then the pandemic happened. I experienced a series of personal griefs that made it hard for me to get up and get out of bed in the morning. And I needed something to get me out of bed, and so I started writing this book.”

We had the pleasure of hosting Vanessa in an author event at Lit Books on 16 March, 2024 where she spoke at length about the intricacies of her novel and writing life. The following are edited excerpts from the hour-long conversation she had with Lit Books co-founder, Elaine Lau and our wonderful audience.

What was the process like turning a short story into a full-length novel?

It was so hard. I had always written short stories before. Short stories are great; they work for my very rigid personality. There are a series of parameters, a timeframe, a limited number of characters. Your story has to end by a certain time.

Writing a novel is like wandering in metaphorical darkness in a forest, and you think you arrive at a lake or something but it’s a mirage. It’s not ended, and you keep wandering. You have to be open to getting somewhere, realizing that may or may not be it, and just continuing to write into the darkness until you reach something else. As a rigid person who loves structure, that was a nightmare. But you just have to write into the chaos and hope for the best, even if you’re like the most detailed outliner in the world. You’ll have to toss that outline aside at some point and be like, let’s start over and figure it out. That was weird for me.

I also chose to write two timelines and four points of views, which was not easy. It was ridiculous. I don’t know why I did.

Some of the stories in this book are from your grandmother. Can you tell us more about that?

My grandma inspired this book and some of the facts came from what she calls a memory book. It was a book where towards the later part of her life, where she was worrying that she was forgetting things, she would write down stories of her life, some of it during the war, some of it pre-war, and some of it post-war. That book was a really wonderful resource for me, both as a writer, but just as a person and a member of this family. I want to note that the book, she always told me, was written for public consumption.

So, some of the stories are from there, but a lot of the stories from this novel are from conversations I had with her growing up. When you don’t finish your food, my grandmother would be like, ‘You know, during the Japanese times, we had to mix in tapioca with our rice because we didn’t have enough to eat.’ There were stories like that, both the ugly and the good, and they just sort of got embedded in my mind. And when I was ready to write it, that’s kind of what came out.

Tell us about how you wrote the characters in this book, starting with the housewife, Cecily. What were you trying to convey with her story?

When I first started writing this book, Cecily didn’t exist. The novel was only about three sad children living through the war because that was what I knew. I knew about children living through the war. That was the experience my grandmother and her siblings had.

I started writing most of this during the pandemic. I was in New York City… And then my mother and my uncle passed away and I couldn’t even go home. I was just filled with grief and rage. I felt robbed of the ability to be with my family, to celebrate the people we loved who had died. And then I’d wake up every day to write about these sad children whose lives are just getting sadder. I needed to give myself a little bit of joy. I needed to give myself something with an element of the ridiculous.

And so, I decided to write about this slightly insane woman who gets to run about all of Kuala Lumpur being a spy. I only wrote her as a spy because I used to really like to watch spy dramas. I was just gonna throw it in there and we can always take it out if it doesn’t work out. I’m gonna give myself some agency via this woman who gets to be irresponsible, make mostly bad decisions, be really, really horny and just do stuff. And that’s what happened. I wrote this character and I guess she stuck because she has since become the central emotional core of the novel. The book has now become a family drama with touches of espionage thriller.

About her morally grey circumstances, I strongly believe that morality is a function of the circumstances we are in. I believe that we don’t know if our principles, our morality, all the things that we believe in will hold if we are faced with the threat of not being able to survive or to have to save our families. We can hope that it is. We can hope that our desire to be kind and wonderful and good does hold. But I don’t always think that is the case. And Cecily, I think, had the best of intentions.

One of the children, Abel, went through a truly harrowing experience in the labour camps. Was it difficult to write these horrific events? Can tell us how you approached Abel’s story arc?

Some of the anecdotes from Abel’s story—who has to live through the camp and who encounters people who cut themselves to use the blood to write and draw memories from the camp in order to make a record of it because they didn’t know if they were going to survive—anecdotes like that, Western audiences often assume are the fictions that I make up. But the truest part of the book is that section because that is a lot of what happened; that was what I was able to research. There’s a fair number of records available because there were a lot of European POWs in those camps.

It was emotional to write, to understand that the 1940s wasn’t that long ago, that people we know had been through something like that. I get asked a lot whether or not I should have made it a little bit less gory or a little bit less confronting. I don’t believe in gratuitous violence, but I believe in honesty.

What do you hope readers will take away from this book?

I want people to remember Cecily, Juju, Abel, and Jasmine’s stories, and that doesn’t mean I want people to remember every plot twist. I hope that audiences remember how they felt when they read the book, because like I said, a lot of our history doesn’t really have a place in the larger canon, and the only way for it to enter the larger canon is if people remember how they felt when they read books like mine, and they talk about it, keep it in the conversation, and remember that experience—because shared experiences make history.

Limited signed copies of The Storm We Made are available in-store and online.